Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Moderator: Loempia

-

Korat

- Volwaardig lid

- Berichten: 228

- Lid geworden op: zondag 07 januari 2007, 02:20

- Locatie: Gelderland/Isaan

Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Een tijdje geleden ging mijn vrouw naar de amphur in Korat om haar ID kaart te vernieuwen. Tot haar verbazing kreeg ze een kaart die levenslang geldig is omdat ze 60+ is  . De moraal: als je partner tegen de 60 loopt en de ID kaart moet worden vernieuwd wacht dan even. Scheelt je weet een tochtje . En oh ja, de kaart is gratis..

. De moraal: als je partner tegen de 60 loopt en de ID kaart moet worden vernieuwd wacht dan even. Scheelt je weet een tochtje . En oh ja, de kaart is gratis..

Pessimisme is verspilde moeite. Het gaat toch fout.

- pjotter

- Volwaardig lid

- Berichten: 767

- Lid geworden op: donderdag 30 september 2010, 17:36

- Locatie: Nakhon Ratchasima Sao Diao

Re: Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Aha. Hetzelfde voor 'onze' roze ID Kaart vanaf 60. 'Talôt Tsjiewiet'

- Herbergier

- Volwaardig lid

- Berichten: 1582

- Lid geworden op: maandag 30 juni 2008, 12:38

- Locatie: Mueang Buriram

Re: Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Dat klopt, ik heb mijn roze ID card al in mei 2016 gehaald en daar staat onderin op de kaart als verloopdatum ook 'Voor het leven'. (Vertaald met Google translate).

Alles van waarde is weerloos.

-

jomel17

- Expat

- Berichten: 1565

- Lid geworden op: zondag 26 november 2006, 18:13

- Locatie: Khon Kaen

Re: Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Ja klopt ik heb mijn kaart net laten lezen door mijn vrouw en zij zegt tot mijn dood . Kaart gekregen in het Thaise jaar 2562

หลงรัก

- pjotter

- Volwaardig lid

- Berichten: 767

- Lid geworden op: donderdag 30 september 2010, 17:36

- Locatie: Nakhon Ratchasima Sao Diao

Re: Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Tja, en wat is levenslang....Ik heb na onze verhuizing van het bestaande huis van mijn vriendin naar een nieuw gebouwd huis in dezelfde straat, toch maar een nieuw geel huisboekje en ID kaart laten maken bij de Amphur met het gewijzigd adres. Overigens alleen het huisnummer wijzigde, ha ha.

- wpdl

- Volwaardig lid

- Berichten: 2900

- Lid geworden op: zondag 05 maart 2017, 07:23

- Locatie: Nakhon Ratchasima

Re: Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Achter op je rijbewijs wat vrijwel iedereen heeft als buitenlander in Thailand staat je adres in het Thais.

Voorkant staan de geschreven gegevens van je reisdocument [paspoort] en naam in onze taal.

Roze ID-kaart was eigenlijk bedoeld voor mensen uit omringende landen, maar om 'discriminatie' te voorkomen mochten alle buitenlanders er een aanvragen.

Zoethoudertje meer is het niet.

Gele boekje valt wat voor te zeggen, hoewel je die gegevens tegen een kleine vergoeding vaak zo bij de Immigratie kan halen.

Een verplicht adres boekje bij jaarvisum aanvraag/ verlenging waarbij een eventuele adres wijziging in hetzelfde boekje gedaan kan worden, net als de Thai zou een stap vooruit zijn.

Adres bevestiging ooit eens een keer nodig gehad [bank] persoonbevestiging, rijbewijs of foto's in je smartphone.

De Thai weet zelf niet wat ze er mee aan moeten met controle, vandaar de overdreven hoeveelheid kopieën overal en nergens.

Voorkant staan de geschreven gegevens van je reisdocument [paspoort] en naam in onze taal.

Roze ID-kaart was eigenlijk bedoeld voor mensen uit omringende landen, maar om 'discriminatie' te voorkomen mochten alle buitenlanders er een aanvragen.

Zoethoudertje meer is het niet.

Gele boekje valt wat voor te zeggen, hoewel je die gegevens tegen een kleine vergoeding vaak zo bij de Immigratie kan halen.

Een verplicht adres boekje bij jaarvisum aanvraag/ verlenging waarbij een eventuele adres wijziging in hetzelfde boekje gedaan kan worden, net als de Thai zou een stap vooruit zijn.

Adres bevestiging ooit eens een keer nodig gehad [bank] persoonbevestiging, rijbewijs of foto's in je smartphone.

De Thai weet zelf niet wat ze er mee aan moeten met controle, vandaar de overdreven hoeveelheid kopieën overal en nergens.

- Ronny010

- Zeer veel ervaring

- Berichten: 127

- Lid geworden op: dinsdag 19 oktober 2021, 05:02

- Locatie: Thailand z.l.a.m.

Re: Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

omringende lande hebben een witte id kaart en geen roze.

zo te zien heb je eer zelf geen? best handig met al je vakanties! overal thaise prijs i plaats van toerist bij parken enz

beide in een paar uur gepiept dus dat is primabello

zo te zien heb je eer zelf geen? best handig met al je vakanties! overal thaise prijs i plaats van toerist bij parken enz

beide in een paar uur gepiept dus dat is primabello

- Herbergier

- Volwaardig lid

- Berichten: 1582

- Lid geworden op: maandag 30 juni 2008, 12:38

- Locatie: Mueang Buriram

Re: Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Een Thais rijbewijs heb ik niet meer, die heb ik wel een voor de auto en een voor de motorbike gehad maar die heb ik in mei 2021 laten verlopen, ik heb ook in Nederland altijd een rijbewijs gehad, maar ik heb al 55 jaar niet meer achter het stuur van een auto gezeten en op een brommer of motorbike heb ik nog nooit gereden, dus heb ik voor het gemak en zeker de veiligheid mijn Thaise rijbewijzen maar laten verlopen.

Op de Thaise roze ID kaart staat op de voorkant in het Thais het ID nummer, je naam, je geboortedatum, huisadres, aanvraagdatum en geldigheidsdatum.

Op de achterkant staat in het Thais de Gedragscode voor ID-kaarthouders.

1 Het is geen identiteitsbewijs.

2 Draag deze kaart altijd bij u ter inspectie.

3 Het is de op de kaart genoemde persoon verboden het kaartuitgiftegebied te verlaten. Behalve voor degene die in het bezit zijn van een vreemdelingenidentiteitskaart of een persoon die schriftelijk toestemming heeft gekregen.

Als je bv bij een bank een rekening wil openen of een wijziging in je account wil laten aanbrengen, heb je niets aan deze roze ID en ook niets aan alleen je rijbewijs waar je paspoortnummer op staat, je hebt dan altijd een geldig paspoort nodig waarvan ze dan de nodige kopieën maken.

Ik gebruik de roze ID bij het inchecken in een hotel of bij andere zaken waar ze om een ID vragen, dat is meestal wel voldoende, een paar jaar geleden vroegen ze zelfs op het postkantoor nog een paar maanden om een ID.

Ik heb vrijwel nooit mijn paspoort bij me, wel mijn roze ID, maar voor de zekerheid heb ik wel een kopie van mijn paspoort en van mijn visumstempel + 90 dagen melding opgeslagen in mijn mobiel.

Hier de ervaringen van buitenlanders die in het bezit zijn van een roze ID.

https://www.thethailandlife.com/pink-id-card

Op de Thaise roze ID kaart staat op de voorkant in het Thais het ID nummer, je naam, je geboortedatum, huisadres, aanvraagdatum en geldigheidsdatum.

Op de achterkant staat in het Thais de Gedragscode voor ID-kaarthouders.

1 Het is geen identiteitsbewijs.

2 Draag deze kaart altijd bij u ter inspectie.

3 Het is de op de kaart genoemde persoon verboden het kaartuitgiftegebied te verlaten. Behalve voor degene die in het bezit zijn van een vreemdelingenidentiteitskaart of een persoon die schriftelijk toestemming heeft gekregen.

Als je bv bij een bank een rekening wil openen of een wijziging in je account wil laten aanbrengen, heb je niets aan deze roze ID en ook niets aan alleen je rijbewijs waar je paspoortnummer op staat, je hebt dan altijd een geldig paspoort nodig waarvan ze dan de nodige kopieën maken.

Ik gebruik de roze ID bij het inchecken in een hotel of bij andere zaken waar ze om een ID vragen, dat is meestal wel voldoende, een paar jaar geleden vroegen ze zelfs op het postkantoor nog een paar maanden om een ID.

Ik heb vrijwel nooit mijn paspoort bij me, wel mijn roze ID, maar voor de zekerheid heb ik wel een kopie van mijn paspoort en van mijn visumstempel + 90 dagen melding opgeslagen in mijn mobiel.

Hier de ervaringen van buitenlanders die in het bezit zijn van een roze ID.

https://www.thethailandlife.com/pink-id-card

Alles van waarde is weerloos.

- wpdl

- Volwaardig lid

- Berichten: 2900

- Lid geworden op: zondag 05 maart 2017, 07:23

- Locatie: Nakhon Ratchasima

Re: Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Het was mij onbekend Ronny dat er meer kleuren ja, zelfs als twee, denk dat de meeste het niet weten ook nooit vermeldt in oudere discussie.

Diegene die het wel weten zullen meer interesse hebben in dat soort zaken zoals jij.

Bij beide documenten zijn er kleine gemak voordelen te halen, klopt, mijn algemene indruk is dat men meer waarde aan beide documenten toeschrijft als dat er te halen valt.

Zoals Herbergier al aangeeft vele zaken moet je toch echt met andere papieren komen wil je een goedkeuring krijgen.

Het verkrijgen van dezelfde documenten zal ook per regio verschillen.

Diegene die het wel weten zullen meer interesse hebben in dat soort zaken zoals jij.

Bij beide documenten zijn er kleine gemak voordelen te halen, klopt, mijn algemene indruk is dat men meer waarde aan beide documenten toeschrijft als dat er te halen valt.

Zoals Herbergier al aangeeft vele zaken moet je toch echt met andere papieren komen wil je een goedkeuring krijgen.

Het verkrijgen van dezelfde documenten zal ook per regio verschillen.

- pjotter

- Volwaardig lid

- Berichten: 767

- Lid geworden op: donderdag 30 september 2010, 17:36

- Locatie: Nakhon Ratchasima Sao Diao

Re: Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Idd, 2 kleuren mij niet bekend Ronny. Waarvan, als farang, is dat dan afhankelijk en waar zou je deze dan kunnen krijgen ? Of is dit mss voor 'permanent residence' mensen ?

idd wpdl, heeft af en toe wat kleine voordeeltjes. In het rijbewijs kantoor (DLT) langs de weg naar Chokchai, geeft men op het gele huisboekje nu alleen maar nieuwe rijbewijzen uit voor 2 jaar helaas. Voor de normale 5 jaar geldigheid moet je dan toch weer naar imm voor een 'certificate of residence'. Tja.

Het grootste voordeel met het gele boekje en ID kaart heb ik gehad toen ik, nu bijna 2 jaar geleden, naar het ziekenhuis (SUTH Universiteits ziekenhuis) moest met Covid. Was nog in de volle strenge tijd hier. Hoefde de rekening van 4,500฿ per dag (12 dagen is toch 54,000฿) niet te betalen. Tja gelukje, niet aan gedacht vantevoren.

idd wpdl, heeft af en toe wat kleine voordeeltjes. In het rijbewijs kantoor (DLT) langs de weg naar Chokchai, geeft men op het gele huisboekje nu alleen maar nieuwe rijbewijzen uit voor 2 jaar helaas. Voor de normale 5 jaar geldigheid moet je dan toch weer naar imm voor een 'certificate of residence'. Tja.

Het grootste voordeel met het gele boekje en ID kaart heb ik gehad toen ik, nu bijna 2 jaar geleden, naar het ziekenhuis (SUTH Universiteits ziekenhuis) moest met Covid. Was nog in de volle strenge tijd hier. Hoefde de rekening van 4,500฿ per dag (12 dagen is toch 54,000฿) niet te betalen. Tja gelukje, niet aan gedacht vantevoren.

- wpdl

- Volwaardig lid

- Berichten: 2900

- Lid geworden op: zondag 05 maart 2017, 07:23

- Locatie: Nakhon Ratchasima

Re: Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Zag het gisteren op een Engels forum staan iets van vijf kleuren al gelang je nationaliteit en aanwezigheid hier.

Weet je gelijk waar je vriendin vandaan komt.

Jouw ziekenhuis verhaal is mij ook onbekend en betwijfel of dat veel met het gele boekje te maken heeft.

Heb er ook wel eens gelegen met tien man op een zaal, foto sessie van de huig tot de krent.

Verzekering betaalde allesbehalve de medicijnen voor thuis.

Het wachten is op de specialist, of is het ook toevallig een weetje, Ronny.

Weet je gelijk waar je vriendin vandaan komt.

Jouw ziekenhuis verhaal is mij ook onbekend en betwijfel of dat veel met het gele boekje te maken heeft.

Heb er ook wel eens gelegen met tien man op een zaal, foto sessie van de huig tot de krent.

Verzekering betaalde allesbehalve de medicijnen voor thuis.

Het wachten is op de specialist, of is het ook toevallig een weetje, Ronny.

- pjotter

- Volwaardig lid

- Berichten: 767

- Lid geworden op: donderdag 30 september 2010, 17:36

- Locatie: Nakhon Ratchasima Sao Diao

Re: Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Aha, nationalteit. Zou idd kunnen bij de voor mij 'onbekende landen' voor zoiets. In mijn kennissenkring, Duitsers, Oostenrijker, Zwitser, Canadees, Engelsman en Zweed, hebben ze allemaal een roze ID  .

.

Pujai baan heeft dat met mijn gele boekje geregeld. Dus ga/ging er vanuit dat dat de reden is/was. Vertelde hij mij teminste nadat ik het van hem terug kreeg. De 2 kamergenoten, (langere termijn toeristen) moesten betalen. Wel via hun verzekering. Ach ja, hebben we achter de rug, ha ha.

Pujai baan heeft dat met mijn gele boekje geregeld. Dus ga/ging er vanuit dat dat de reden is/was. Vertelde hij mij teminste nadat ik het van hem terug kreeg. De 2 kamergenoten, (langere termijn toeristen) moesten betalen. Wel via hun verzekering. Ach ja, hebben we achter de rug, ha ha.

wpdl schreef: ↑woensdag 06 december 2023, 03:08 Zag het gisteren op een Engels forum staan iets van vijf kleuren al gelang je nationaliteit en aanwezigheid hier.

Weet je gelijk waar je vriendin vandaan komt.

Jouw ziekenhuis verhaal is mij ook onbekend en betwijfel of dat veel met het gele boekje te maken heeft.

Heb er ook wel eens gelegen met tien man op een zaal, foto sessie van de huig tot de krent.

Verzekering betaalde allesbehalve de medicijnen voor thuis.

Het wachten is op de specialist, of is het ook toevallig een weetje, Ronny.

- wpdl

- Volwaardig lid

- Berichten: 2900

- Lid geworden op: zondag 05 maart 2017, 07:23

- Locatie: Nakhon Ratchasima

Re: Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Las in de http://mekongmigration.org/?p=5545 dat je met een roze id card geen grensoverschrijdende acties kan doen en met een groene wel dus die verstrekt men schijnbaar aan mensen die hier werken en hun Thuisland aan de Mekong hebben en zo af en toe eens naar huis willen.

Dat zulk soort 'voordelen' gelijk wat meer mag kosten is duidelijk in het onderwerp.

Dat zal dan ook wel zoiets zijn met andere regio, het feit wat je er mee kan doen behalve je ID.

Het Europa, Verenigde Staten en down-under zal wel een pot nat zijn voor de Thai.

Ronny heeft het druk denk ik.

Dat zulk soort 'voordelen' gelijk wat meer mag kosten is duidelijk in het onderwerp.

Dat zal dan ook wel zoiets zijn met andere regio, het feit wat je er mee kan doen behalve je ID.

Het Europa, Verenigde Staten en down-under zal wel een pot nat zijn voor de Thai.

Ronny heeft het druk denk ik.

- Ronny010

- Zeer veel ervaring

- Berichten: 127

- Lid geworden op: dinsdag 19 oktober 2021, 05:02

- Locatie: Thailand z.l.a.m.

Re: Levenslang geldige ID kaart voor Thai

Kaarten in overvloed, onderaan nog wat foto's

Contested Citizenship: Cards, Colors and the Culture of Identification1

Pinkaew Laungaramsri

Introduction

On Friday September 8, 2005, more than 800 villagers from border communities of Tha Ton subdistrict, Mae Ai district, Chiang Mai province gathered before the Administration Court building in Chiang Mai as they listened to the reading of a verdict which ruled that a Mae Ai district office order to remove the name of 1,243 villagers from the household registration was unlawful. The court verdict came as a result of many years of local effort to regain their citizenship after it was revoked by the district office in February 2002. For Mae Ai district officials, the rationale for such revocation was based on their belief that these people were not “Thai.” This is simply because these people have never been permanent residents, as they constantly cross the borders between Thailand and Burma. Some of them have even obtained “the pink card,” the identification card for displaced person with Burmese nationality. Local people, however, argued that they once had the Thai ID card before moving out of the villages due to political turbulence between the Burmese army and ethnic insurgency in that area in 1971. Since they lost the Thai ID cards, their subsequent acquisition of “the pink card” was because of fear of deportation. District and local disputes went on for several years with no progress, as all the relevant documents stored at the district office which could have been used for verification were burned up in a 1976 fire accident. As a result, the Tha Ton villagers had no choice but to file a lawsuit against the Local Authority Department, and it was successful.

1 In Ethnicity, Borders, and the Grassroots Interface with the state: Studies on Mainland Southeast Asia in Honor of Charles F. Keyes, John Amos (ed.), Silkworm Books, Forthcoming

1

The politics of identification cards in the Mae Ai case is representative of the unsettling relation between state and citizenship in the border area. Over the past three decades, cards have become the strategic tool used by the state to differentiate the Thai from the non-Thai other. Issuance and revocation of cards for border-crossing people have become common state practices. At the same time, amendments of the Nationality Act are enacted now and then, changing the legal definition of a Thai citizen. As more colors have been assigned to new identification cards, cards and confusion about them increasingly complicate the interaction between state and people. And widespread card dispute and scandal proliferate.

In tracing the geneology of the scientific modes of classification of ethnic differences used by the modern nation-state in Asia, Keyes maintains that the political application of such science has not only resulted in the production of hierarchical order but also the fixing of national and thus ethic boundaries (Keyes 2002). These ethnological projects of classification undertaken in various countries of Asia, though based on flawed assumptions, have served as a powerful tool in differentiating between the national and the ethnic other. I would argue further that the ways ethnic classifications become operational in a society, as both tools of the state and a sign of its capacity, depend on an effective methodology. As Scott (1998:2-3) suggests, the modern state’s project to appropriate, control, and manipulate the cultural diversity of its inhabitants is carried out through tools of simplification and legibility, by “rationalizing and standardizing what was a social hieroglyph into a legible and administratively more convenient format" (p.2-3). In the case of Thailand, I maintain that a methodological tool that has powerfully rendered ethnic diversity legible is the system of identification cards, which serves a dual function of national embrace and dis-embrace. A product of the cold war era, such a system is not

2

merely a means by which the state controls populations but is constitutive of the sovereign nation-state itself. By tracing the history of the identification card system and shifting ideas of citizenship, this paper explores the changing relations between the state and its subjects. Inconsistent functions and meanings of cards assigned to different groups of people reflect the state’s unstable notions of citizenship and anxiety towards mobility. Who counts as “members” and as “different,” and where and when difference may legitimately be represented, are historically contingent. In the case of Thailand, the inherent instability in both the meaning and the limits of citizenship identity and difference is well-illustrated at the border whereas shifting card practices reveal the constant negotiation between forces of normalization and differentiation, and of national security and economic liberalization. As the state’s attempt to define people is often incomplete, the deployment of the state’s methods of identification among the people so designated always implies tension and contestation. Re-appropriation and reinterpretation of identification cards has been a strategic means of negotiation by the people classified as the non-Thai other. It is in this context that the notion of citizenship is often problematic, while the project of classifying and defining peoples will thus forever remain, as Keyes argues, “work in progress” (2002:1194).

The Embracing Citizenship

When the idea of citizenship was first introduced in Thailand in the early twentieth century, it was not really clear what it meant. Since the reign of King Chulalongkorn, colonial expansion has made it inevitable for the Siamese elite to rethink the once diverse ethnic conglomeration of Siam as a homogenous Thai nation, employing a European ideology of race. The creation of Thai nationality was carried out in the form David

3

Streckfuss calls “reverse-Orientalism”—the transformation of the other into Thai as a form of resistance against European colonialism. The materialization of “Thai nationality” was carried out by the subsequent King Vajiravudh (Rama VI). Interestingly, what concerned him was not how to define citizenship but rather how to turn the non-Thai subject into a Thai citizen. The Naturalization Act was then implemented in 1911, prior to the first Nationality Act in 1913. As Saichol (2005) notes, competing Chinese nationalism, widespread among overseas Chinese in Siam, was alarming, and one way to suppress the increasing mobilization and politicization of Chinese nationalist sentiment was through assimilation. The significant requirement of official naturalization was that those eligible to be citizens had to prove they had had at least five years residency in the Kingdom. At the same time, offspring of those with approved citizenship were automatically eligible to become citizens.

In the reign of King Rama VI, assimilation through legal naturalization served as a means to orient the people who the King defined as “born as Thai, being Chinese as vocation, registered as English” (Saichol, ibid.) and to transform them into Thais in soul and spirit. Legal naturalization was a characteristic strategy of “Thai-ization” (kan klai pen thai) and a state attempt at monopolization of the Thai nationalism. In keeping with the trajectory of transforming the multi-ethnic kingdom into an exclusive nation-state, the newly modern Thai state has continued to define Thai nationality by cultural qualities associated with the three elements of Thai language, Buddhism, and loyalty to the King. However, such effort at the homogenization of Thai national identity did not receive much of support by the Chinese, who constantly challenged the hegemonic notion of the Thai nation and thus rendered the project of assimilation problematic.

4

Despite the widespread propagation of Thai nationalism, Thailand’s 1911 Nationalization Act and 1913 Nationality Act did not define citizenship, nor its rights and obligations. If citizenship means “full membership in the community” (Marshall 1950), the nature of the legal bond between the members and their Thai community and an elaboration of what legal status of membership means is absent from the text. In the early period, citizenship was a somewhat ambiguous notion of incorporation that did not yet enter the realm of administrative apparatus. Although, a naturalization certificate was issued, it was not a national identification document and was not used by the state as a means for identity control. State’s attempt to regulate movement across national boundaries was also in its infancy. The unsettling notion of a means of embracing citizenship, with loosely regulatory mechanisms, thus allowed for the possibility of interpretation and negotiation. As a result, for non-Thai, particularly Chinese, to be Thai or not to be Thai remained a political and cultural choice which could be maneuverable. . However, such possibility became increasingly difficulty with the development of a state identification card system in the middle of the twentieth century.

Culture of Identification and the Proprietary Citizenship

Since 1932, in the post-absolute monarchy era, official thinking about citizenship has undergone a significant shift. Under the regime of Phibun Songkram, Thai race (chonchat thai) had been emphasized as the significant trait of Thai nationality. The emphasis on Thai race as the basis of nationalism served multiple purposes--to undermine the previous idea of Thainess centered around the allegiance to the monarchy, to exclude

5

the Chinese from the political sphere, and to provide a protective ring against communist expansion (Saichol 2005, Keyes 2002). At the same time, the dream of a unified Thai nationality extended across national boundaries, culminating in a short-lived pan-Thai movement (see Keyes 2002, Crosby 1945). It was also in the reign of Phibun Songkram that “Thai” was turned into an official identity making people’s identities and nationality within the boundary of the nation-state. In 1939, Siam was renamed Thailand, the country that defined “Thai” as its culture, citizenship, and territory. In 1943, the regime launched a first experimental identification card, authorized by the Identification Card Act. This card applied to Thai who resided in Pranakorn (Bangkok) and Thonburi provinces.

The invention of Thai identity cards used in conjunction with the household registration document represents a new method of the Thai state authority to circumscribe, register, regiment, and observe people within their jurisdictions. The identification card as a form of state power was necessary not only because of the bureaucratic control it entailed, but also because it implied the establishment of citizenship by binding body, identity, and citizenship together. It is worth noting that state inscription on population is by no means a recently modern project. In pre-modern Siam, the most effective control of corvee labor was carried out through methods of body marking, the tattooing of the wrist of a phrai luang (commoner who worked for the King), identifying the name of city and master.

Unlike tattooing and other pre-modern forms of registration, the purpose of modern state inscription through identification card is not for labor control but to ensure the national loyalty of the subject of the state. The card has also brought with it the notion of proprietary citizenship that allows the state to maintain direct, continual, and specific contact between its ruling bureaucracy and its citizenry. However, one enduring problem

6

the state faced in constructing a system of official identification was how to articulate identity to a person/body in a consistent and reliable way. As body and identity has never been in permanent or fixed connection, the task of describing identity accurately and consistently was a major challenge to the state. Thorough technologies must then be designed to facilitate the identification process. Binding identity to the body was thus done by technologies which included photographs, signatures, and fingerprints, and by the use of legal practices, for example, the requirement to carry identification cards at all time.

Picture 1: The first Thai identification card (1943)

Picture 2: The second Thai identification card (1963)

7

8

Picture 3: The third Thai identification card with 13 digits (1988)

Picture4: The fourth Thai identification card with magnetic stripe(1996)

Picture 5: The smart card (2006)

The state’s notion of proprietary citizenship through the enforcement of identification cards has not only served to fix identity and loyalty as subject to one nation- state, but has also been used as a powerful tool to discipline stubborn/bad subjects. In the history of suppression tactics, identification card inspection has been employed as a state’s means of surveillance and punishment against popular demonstrations and political movements. The historical construction of official Thai identity epitomizes the state’s attempt to establish a form of ownership over individual citizens, reflected in different technologies of identification. Proprietary citizenship has been exercised through the making of a permanent, indelible identity which is lasting, unchangeable, always recognizable and provable. Identification cards as a function of state capacity to create documentary evidence and bureaucratic records have enabled the state to recognize specific individuals. Official Thai identity acquires its meaning and power not only through the system of classification but also through the active interactions with the state machinery which constantly monitors, regulates and guides personal conduct, thus legitimizing the state’s intimate bond with its citizen.

Cards, Colors and the Contingent Citizenship

Although citizenship is commonly regarded as a matter of the relations between individuals and the state to which they belong, it is also one of the markers used by states in their attempt to regulate the movement of people across borders. Citizenship at the border is often historically volatile, reflecting the state’s changing view towards border and mobility. In its transformation towards the modern nation-state, government of people gave way to government of territory, so the need for clearly bounded divisions of ownership and control correspondingly increased, with the border becoming a state weapon (Wilson and Donnan

9

1998:8-9). Nevertheless, the effective control of territory also depends on the way in which identity can be effectively regulated.

Despite the fact that immigration has been always central to the process of nation- building, the historical connection between route and root (Clifford 1997) as basis of societal formation has often been written out of the collective memories of the modern nation-state. Fluid boundaries have been suppressed by territoriality as one of the first conditions of the state’s existence, and the sine qua non of its borders (Wilson and Donnan 1998). As Castles and Davidson (2000) note, the regulation of immigration is only a recent phenomenon, dating from the late nineteenth century, while state policies to integrate immigrants or regulate ‘community relations’ date only from the 1960s. Yet, assimilation and differential exclusion have been made natural and inevitable processes of what Castles and Davidson call the controllability of difference (ibid.).

Whereas borders represent spatial and temporal records of relationship between people and state, such records often include the state’s anxiety towards mobility across national boundaries. Contingent citizenship is therefore a product of shifting state-ethnic relations at and across borders as mediated by diverse ideological and political economic forces at different periods of time. Such forces, which oscillate between inclusion and exclusion, have been played out both symbolically and concretely, constituting a “politics of presence,” as “an embodied enactment of toleration or intolerance” (Yuval-Davis and Werbner 1999:4). In the case Thailand, the politics of presence is well illustrated in the complex yet arbitrary systems of identification cards at the border.

The post-World War II borders of Thailand can be characterized by a tension

10

between national security ideology and forces of economic integration. Between 1965- 1985, borders have become highly politicized with the migration influx of refugees, displaced people, and political asylum seekers. On the Thai-Burmese border, the Thai state indirectly supported the armed forces of ethnic minorities that were fighting the government of Burma, as a kind of “buffer state” (Caouette, Archavanitkul, and Pyne 2000). The security policy of this period was designed in order to prevent the invasion of communism from nearby countries (ibid.). It was in this period that the so-called “colored cards” (bat si) were designed as a means of securing the borders through certifying individual identity and controlling movement across the border. Most of these diverse identification card programs were poorly planned and lacked consistent rationales (e.g., what counts as immigrant can vary depending on date of entry into Thailand, ethnic identity, and political history), resulting in confusion rather than effective measures of control. Throughout the two decades of “colored cards” and registration of people classified as non-Thai others, the implementation of differential exclusion has often been in a state of flux. For example, some cards might be eliminated, leaving the card holders with no future, while others were upgraded to a Thai identification card. After 1989, with the waning of the cold war era, borders acquired new meaning as a gateway to economic integration. New types of cards have been invented for “alien labor” (raeng ngan tang dao), as a means to both regulate the flow of cross-border immigrants and reap benefits from new economic resources. While controversy regarding alien identity cards has escalated and the demand for Thai identification cards among hill people and migrant workers has intensified, “ID card scams” have become widespread, adding further chaos to the colored card scheme.

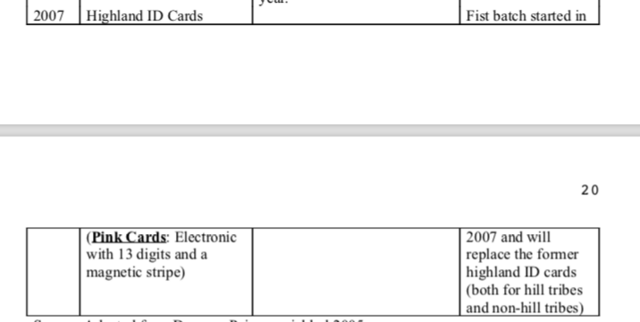

Table 1 Chronology of Implementation of “Colored Cards” for Non-Thai Citizens in Thailand

11

1969- Hill Tribe Coins 1970

1970 Former Kuo Min Tang Soldier ID Cards

(White Cards)

No longer in use.

Issued by Depart of Administration

Cabinet Resolution on 6/10/1970 assigned immigrant status to former KMT soldiers. Cabinet Resolution on 30/05/1978 allowed legal naturalization of former KMT soldiers for their contribution to the Thai nation (fighting communists).

Cabinet Resolution on 12/06/1984 allowed children of former KMT soldiers to

Used as verification of settlement in Thai Kingdome between 1969- 1970.

Widespread selling of coins and difficulty in establishing proof. Three batches of IDs have been issued.

12

Year

Identification Cards

Status

1967

Vietnamese Refugee ID Cards (White Cards with a Blue Border)

Children of Vietnamese Refugees who entered into Thailand between 1945-1946 were eligible for Thai citizenship.

Vietnamese refugees who have not acquired Thai citizenship must ask permission from governors before traveling out of residential provinces.

Issued by Police Department

1st batch

Issued :24/08/67 Expired:23/08/1973 2nd batch Issued:2/08/1980 Expired:1/08/192 3rd batch extended 2nd batch to 3/12/1988

4th batch

Issued: 19/07/1990 Expired:18/07/1995 5th batch Expired:26/08/1997

13

1976 Immigrants with Thai Race from Ko Kong,

Cambodia

(Green Cards)

acquire Thai citizenship. Those who have not yet acquired Thai citizenship must ask permission from governors before traveling out of residential province.

Issued for former Thai citizens and their children whose citizenship was removed when Ko Kong was returned to Cambodia.

Three batches were issued between 1976-1989

1977

Illegal Immigrants (with Thai Race) from Cambodia

(White Cards with Red Border)

As of present date, no official status has yet been assigned.

Immigrants with Thai race from Cambodia who entered into Thailand after 15/11/1977. Thai government has used this date to separate legal from illegal immigrants from Cambodia. Most of this group resides in Trad Province.

14

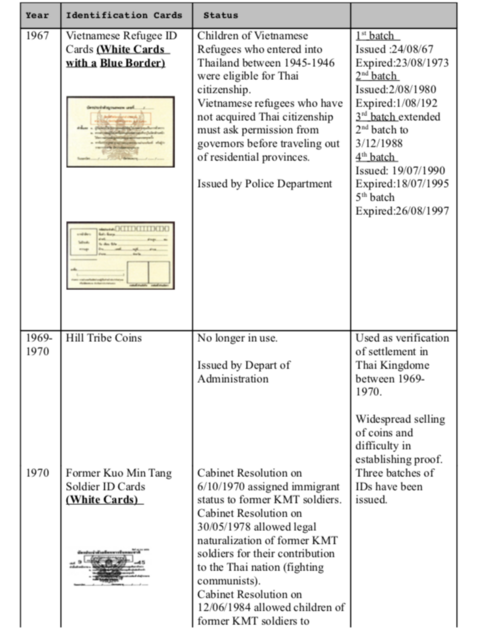

1978

Displaced Person with Burmese Nationality ID Cards

(Pink Cards)

Cabinet Resolution on 29/08/2000 assigned alien status to Pink Card holders. Children of this group born between 24/12/1972- 25/02/1976 were eligible for Thai citizenship.

Three batches were issued between 1976-1993) for ethnic groups from Burma who entered into Thailand before 9/03/1976

1984 Haw Chinese Immigrant ID Cards

(Yellow Cards)

Cabinet Resolution on 21/06/1984 assigned the status of legal immigrants to those who entered into Thailand between 1950-1961.

Children of Haw Chinese immigrants whose citizenship were removed are eligible to regain their citizenship.

Four batches were issued.

This card is applied to former soldiers of KMT and their families who entered into Thailand

between 1950-1961 and could not return home country for political reason. These immigrants resided mainly in Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, and Mae Hong

15

1987

1988

Nepalese Immigrant ID Cards

(Green Cards)

Independent Haw Chinese ID Cards (Orange Cards)

Formerly classified as Displaced Person with Burmese Nationality.

Cabinet Resolution on 29/08/2000 assigned a status of legal immigrant and children who were born between 24/12/1972-25/02/1992 were eligible for Thai citizenship.

Cabinet Resolution on 27/12/1988 assigned a temporary residential status. Cabinet Resolution on 29/08/2000 assigned a legal immigrant status for those who entered the country before 3/10/1985, and illegal status for those who entered afterwards. Children who were born between 14/12/1972- 25/02/1992 are eligible for Thai citizenship.

Son provinces.

Entered into Thailand in Thong Pha Bhum, Kanchanaburi Province.

Entered into Thailand between 1962-1978.

This card is applied to relatives of former soldiers of KMT who migrated into Thailand between 1962- 1978.

16

1989- 1990

Former Malayu Communist ID Cards (Green Cards)

Cabinet Resolution on 30/10/1990 assigned legal status and granted citizenship to children who were born in Thailand

1990- Highlander ID Cards 1991 (Blue Cards)

Approved by Cabinet Resolution on 5/06/1999. Highlanders are classified into two types: 1. nine groups of hilltribes

2. non-hilltribes, e.g.,Shan, Mon, Burmese, etc. Legal status are granted to those who entered into Thailand before 3/10/1985 and are eligible for Thai citizenship. Children of those who entered before 3/10/1985 and born between 14/12/1972- 25/02/1985 are eligible for Thai citizenship.

Surveyed and registered by District and Dept.of Administration.

17

1991

Malbri ID Cards

(Blue Cards)

Classified as “highlanders”, considered as indigenous people of Phrae and Nan provinces. Entitled to Thai citizenship.

1991

1991

Displaced Person with Thai Race and Burmese Nationality

(Yellow Cards with Blue Border)

Laotian Immigrant ID

The Thais who resided at the borders between Siam and Burma before boundary demarcation in the reign of King Rama V. and refused to move across the border after the demarcation finished. Political tension between SLORC and ethnic insurgency along the borders resulted in the movements of these Thais into Prachaub Kirikhan, Chumporn, Ranong, and Tak provinces.

Cabinet Resolution approved the naturalization of the people who entered into Thailand before 10/03/1976.

The Laotians who moved to

First batch used the same card with Displaced Person with Burmese Nationality but added a stamp indicating “with Thai Race.”

First batch used the

18

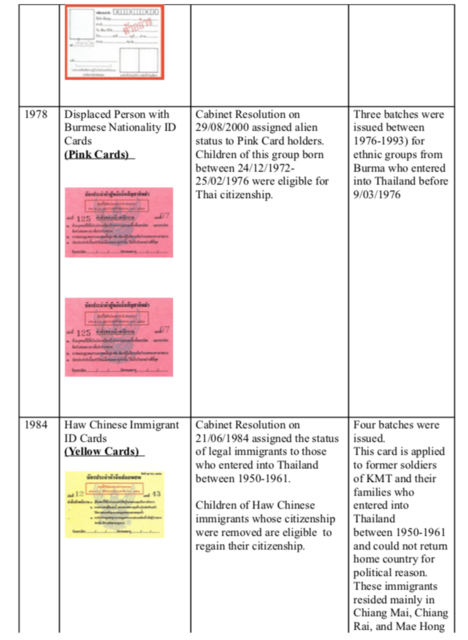

Cards

(Blue Cards)

live with relatives in Nongkhai, Ubon Ratchathani, Loei, Nakorn Phanom, Mukdaharn, Utaradit, Chiang Rai, and Nan provinces (not the ones in refugee camps).

As of present date, no official status has been assigned. Children are not eligible for Thai citizenship.

Issued according to policies by the National Security Council and the Second Regional Army.

Highlander ID Cards (crossing Highlander and adding Laotian Immigrant), due to limited budgets).

1994

Thai Lue ID Cards

(Orange Cards)

Considered as Thai race originally resided in Sipsongpanna, Yunnan, China. Cabinet Resolution on 17/03/1992 assigned a legal immigrant status.

Children born in Thailand are eligible for Thai citizenship.

Two batches were issued.

Formerly classified in the same group as Displaced Person with Burmese Nationality (Pink or Blue Cards).

1996

Hill Tribe outside Residential Area ID Cards (Hmong refugees in Tham Kabok, Saraburi

Will be deported to third countries.

Two batches were issued.

Population: 14,602

19

province)

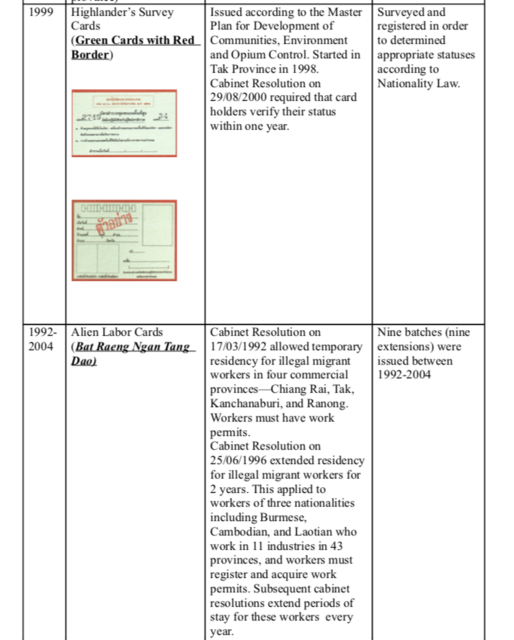

1999

Highlander’s Survey Cards

(Green Cards with Red Border)

Issued according to the Master Plan for Development of Communities, Environment and Opium Control. Started in Tak Province in 1998.

Cabinet Resolution on 29/08/2000 required that card holders verify their status within one year.

Surveyed and registered in order to determined appropriate statuses according to Nationality Law.

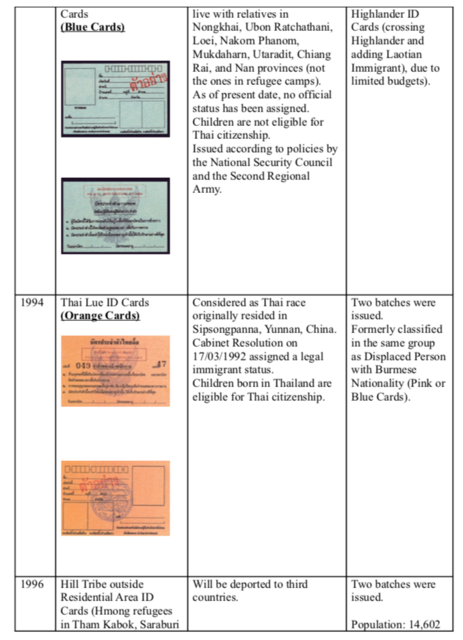

1992- 2004

2007

Alien Labor Cards

(Bat Raeng Ngan Tang Dao)

Highland ID Cards

Cabinet Resolution on 17/03/1992 allowed temporary residency for illegal migrant workers in four commercial provinces—Chiang Rai, Tak, Kanchanaburi, and Ranong. Workers must have work permits.

Cabinet Resolution on 25/06/1996 extended residency for illegal migrant workers for 2 years. This applied to workers of three nationalities including Burmese, Cambodian, and Laotian who work in 11 industries in 43 provinces, and workers must register and acquire work permits. Subsequent cabinet resolutions extend periods of stay for these workers every year.

Nine batches (nine extensions) were issued between 1992-2004

Fist batch started in

20

(Pink Cards: Electronic with 13 digits and a magnetic stripe)

2007 and will replace the former highland ID cards (both for hill tribes and non-hill tribes)

Source: Adapted from Darunee Paisanpanichkul 2005

Since 1967 there have been at least 17 different kinds of ID cards imposed on the different groups of immigrants who entered into Thailand in different periods of time and with different reasons. The system of identity designation by cards is rather chaotic, inconsistent, and arbitrary. While different deadlines of entry into Thailand have been set to differentiate Thai from non-Thai citizens, types of immigrants were unevenly categorized, using random criteria of ethnicity, political ideology, or elevation. Discursive policies regarding border and border crossing have also been present. At a time of political pressure shaped by an ideology of national security, the attitude towards immigrants was restrictive, resulting in an assertion of clear separation of members of different categories from others, “us” from “them.” However, in periods of economic liberalism and national prosperity, policy often entails permissive approaches towards population movement and political rhetoric about the importance of open borders. Immigration policies today are still characterized by the shifting motivations of the state, between limiting its obligation toward immigrants and ensuring the availability of human resources the immigrants supply to the Thai economy. As a result, restrictions on temporary residency and alien labor ID cards have become more extensive every year, with fees required by state agencies increasing.

Contested Citizenship and the Everyday Practice of ID Cards

Writing from a feminist perspective, Werbner and Yuval-Davis (1999) propose to look at citizenship as a contested terrain. As unsettling collective forces, the degree to which the political agency of subjects determines or is determined by such forces is key to everyday politics of citizenship. As they argue, rather than being simply an imposed political construct of identity, citizenship as a subjectivity is “deeply dialogical, encapsulating specific, historically, inflected, cultural and social assumptions about similarity and difference” (p.3). Negotiating citizenship has brought about different cultures of identification in which the relationship between state and citizen and the non-citizen other is re-interpreted.

Everyday practice in the use of identification cards by Thai and non-Thai citizens challenges claims to authority in determining who belongs to the nation-state and who does not, as a central component of sovereignty. Throughout the history of citizenship making, wherever identification cards have been invented and implemented--as the state attempts to classify subjects residing within or attempting to enter state territories by controlling their mobility and demanding--total allegiance--such attempts have also been contested by local people. Various card practices ranging from discarding/returning the cards (khuen bat prachachon), burning the cards (phao bat prachachon), or refusing to apply for identification cards have become a symbolic protest against the hegemonic idea of what it means to be “Thai.” For over three decades, as the state has attempted increasingly to enforce the ID card system, the cards have also been turned into a battlefield by marginal groups in negotiating their position with the nation-state. The performative character of cards has become a subversive tool of local critique against a government which is often

21

indifferent or weak in taking care of poor and marginal communities. Some examples of grassroot’s political practice of ID cards are illustrated below.

Three hundred farmers from the People’s Network in 4 Regions have decided to call off their demonstration after camping in front of the government house since 12 March 2007. The demonstration did not receive any clear answer from the government regarding the way to solve their debt problems. The group which included elderly and children showed their disappointment pertaining to the Cabinet Resolution on 27 March which did not issue any measurement relating to their problem. It was clear that the government was not only unresponsive but also indifferent to local demand. The group has then planned to march to meet the members of the National Legislative Assembly before walking on foot to Lao PDR in order to set up a Center of Stateless People and will ask for a permission to reside there. Before entering into Lao PDR, the group will return their ID cards to the Thai government at the immigration office at the border.

Daily News 28/03/2007

If (the government) passes this (National Security) Act, there will be two states ruling the country. The constitution will be meaningless... (We) will have to fight forcefully...particularly, the Human Right Commission and academics must join together in resigning (from members of National Legislative Assemby)... We must stage a symbolic protest. If (the Council for National Security) refuses to stop, (we) must turn down the 2007 Constitution, though it has improved from the one in 1997. For the people, they must join together in the burning of identification cards as a strategic means to reject the power of the dictatorship.

22

Pipob Thongchai, member of the Committee for the Campaign for Democracy (08/2007)

If citizenship is a product of the creation of the modern nation-state, one of the great paradoxes of such construction is that the process of control and constraint entails also constitutes a moment of emancipation. Like all hegemonic discourses, modern citizenship has never been absolute. While the identification card is fundamental to proprietary citizenship, it has been re-appropriated and used as a dialogical tool by people in expanding participatory politics which call for a righteous state. It is within this terrain that autonomy and the right to be different are pitched against the regulating forces of the state identification system and its demand for definite national belonging. Like state-formation itself, constructing citizenship has been not only a problematic and unfinished process of defining boundaries and identities but also a project of reworking social and political practices.

One interesting arena of local reworking of citizenship is at the border. As a counter-construction of citizenship (Cheater 1999), border crossing and multiple identities practiced by both individuals and families undermine the rhetoric of unified solidarity and singular national identity. In his study of ethnic minorities at the Thai and Malaysian borders, Horstmann (2002) notes that dual citizenship and the holding of multiple identification cards constitute an important strategy employed by the “trapped minorities” in response to the state’s rigid boundary surveillance and citizenship policy. Multiple citizenship rights have been acquired by these minorities through various means, including the registration of children’s birth at a location across the border, marriage, making use of kinship relations or inventing them, and applying for naturalization. Horstmann argues that

23

the adoption of dual citizenship not only reflects the plurality of local social life, but has played a long historical role in relations between the social worlds of Thai and Malay communities cutting across national identities (ibid.). Border populations therefore use the documents of the state to their personal advantage, producing their identity cards to facilitate border crossings.

Similar practices are also found among members of border communities and immigrants along the border between Thailand and Burma, where identities are fixed by different kinds of “colored identification cards.” Arranged adoption of children of immigrant parents from Burma whose legal status remains uncertain by Thai citizens is a fast-lane strategy to guarantee permanent citizenship for the youths. Through adoption strategy, young children will also be able to have access to a better education, as they are entitled to with Thai citizenship. As different kinds of identification cards for immigrants are issued every year in different provinces and with different purposes, with no clear information about which cards will promote a more promising status, acquisition of multiple “colored cards” has been a speculative strategy among individual migrants. In my interview with a family of Piang Luang village, a border community between the Shan states in Burma and Wiang Haeng District in Thailand’s Chiang Mai province, four members in the same family, including father, mother, and two children, have obtained three different kinds of identification cards. While still residing in Chiang Rai province, the father used to have a “yellow card” (Haw Chinese Immigrant ID Card), the status to which he is entitled as a son of a former KMT soldier. After getting married to his wife, who lives in Wiang Haeng district, he has not decided to abandon the “yellow card” but is now applying for a “pink card” (new electronic highlander ID Card). According to him, the

24

“yellow card” does not have any future. His wife has had a “pink card” since she moved into Thailand. The two children, however, have been adopted by two different Thai families and thus have different last names from their parents and from each other.

For ethnic minorities at the border and immigrants from Burma alike, colored identification cards have become assets with different kinds of value which have been accumulated and used to upgrade their status. The process of obtaining these cards is of course illegal and involves various schematic scams. Some ethnic hill people who have settled in Thailand long enough might work as brokers who travel to many villages in order to buy Thai ID cards from relatives of the deceased and sell them to the new immigrants. Many Shan immigrants from Burma who have no card of their own might make deals with friends in the hill village, adding their names into the house registration documents in order to obtain ID cards for highlanders. It is common that people who live at the border or in a refugee camp such as the one in Mae Sot district, Tak province might carry more than one card and use each of them for different purposes. ID cards are therefore not only the state instrument of control but survival resources to be assessed, classified, and circulated according to a hierarchy of values which is usually predicated on the degree to which a given card can be turned into Thai citizenship and how much freedom of mobility it entails. Immigrants who have no cards are often considered as the poorest and most marginal, because if they are arrested they can be immediately deported to their home countries. The “alien labor card” (work permit for illegal immigrants) is considered as valueless as it allows only limited freedom of mobility. A migrant worker with this card is prohibited from traveling outside the vicinity of the work place. As a result, the person who holds the “alien labor card” will try at best to obtain a more “valuable” card which allows more freedom of

25

movement, such as a green card with red border, a pink card, or even a Thai nationality card. Negotiating mobility has thus been an integral part of redefining citizenship among immigrants and members of border communities in Thailand.

Conclusion

In this chapter, I have tried to capture the shifting and conflicting constructions of citizenship and its complex apparatus of ID card systems. I have argued that the culture of identification in Thailand is characterized by its tension and contradiction, the product of the interplay between shifting official forms of domination and control and minorities’ experimentation and everyday practice.

The state’s chaotic system of classification of nationality is often actively learned and re-interpreted in the local understanding of citizenship. While state differentiation between Thai nationals and alien others has long been integral to the process of nation- building such attempts have often been contested. Informal politics thus plays a crucial role in shaping citizenship discourse among the Thai as well as among non-Thai immigrants. Cards and colors, as a powerful technique of statecraft deployed to control mobility and fix the identity of border-crossing people, have often been employed by the non-Thai subjects as assets for circulation and tools for negotiation. The population of immigrants has been turned arbitrarily into an ambiguous ethnic category of non-Thai minorities; such transformation has often been in flux, resulting in diverse translations of everyday-life notions of citizenship. Contested citizenship constitutes therefore a reworking of national identification as something alive and exciting--involving a multiplicity of actors struggling in an enlarged political sphere extending beyond the constrictions of legality. It is in this realm that the non-Thai other is allowed the possibility of being both subjectified and

26

subject-making in the unstable state-ethnic relationship of modern Thai society.

27

References

Caouette, Theresa, Kritaya Archavanitkul, and Hnin Hnin Pyne (2000) “Thai Government’s Policies on Undocumented Migration from Burma,” in their Sexuality, Reproductive Health, and Violence: Experiences of Migrants from Burma in Thailand, Mahidol University: Institute for Population and Social Research.

Caplan, Jane and John Torpey, eds. (2001) Documenting Individual Identity: The Development of State Practices in the Modern World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Castles, Stephen and Alastair Davidson (2000) Citizenship and Migration: Globalization and the Politics of Belonging. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Cheater, A.P. (1999) “Transcending the State? Gender and Borderline Constructions of Citizenship in Zimbabwe.” In Border Identities: Nation and State at International Frontier. T. Wilson and H. Donnan, eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clifford, James (1997) Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century, Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press.

Darunee Paisanpanitchakul (2005) “Right to Identification Paper in Thai State.” Unpublished MA Thesis, Thammasat University (in Thai).

Feeney, David (1989) “The Decline of Property Rights in Man in Thailand 1800-1913.” The Journal of Economic History 49(2): 285-296.

Gates, Kelly (2004) “The Past Perfect Promise of Facial Recognition Technology.” Occasional Paper, ACDIS, June.

Horstmann, Alexander (2002) “Dual Ethnic Minorities and Local Reworking of National Citizenship at the Thailand-Malaysian Border.” Center for Border Studies, Queens

28

University of Belfast.

Keyes, Charles (2002) “The peoples of Asia’—Science and Politics in the Classification of Ethnic Groups in Thailand, China, and Vietnam,” The Journal of Asian Studies 61(4): 1163-1203.

Krisana Kitiyadisai (2007) “Smart ID Card in Thailand from a Buddhist Perspective,” http://www.stc.arts.chula.ac.th/cyberet ... mart%20ID- buddhist.doc (28/11/07).

Marshall, T. H. (1950) Citizenship and Social Class. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Matsuda, Matt K. (1996) The Memory of the Modern. New York: Oxford University Press. Nitaya Onozawa (2002) “The Labor Force in Thai Social History,” www.tsukuba-

b.ac.jp/library/kiyou/2002/3.

Pittayalonkorn, Prince (1970) “Chat and Araya” Pasompasan Series 3. Bangkok:Ruam San, Pp.141-142. (in Thai)

Rabibhadana, Akin (1970) The Organization of Thai Society in the Early Bangkok Period 1782-1873. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Saichol Satayanurak (2005) “The Mainstream Historical Thought about Thai Nation.” In The Historical Thought about Thai Nation and the Community Thought. Chattip Natsupa and Wanwipa Burutrattanapan, eds. Bangkok: Sangsan (in Thai).

------ “The Construction of Mainstream Though on ‘Thainess’ and the

29

‘Truth’ Constructed by ‘Thainess’.” Sarinee Achavanuntakul, tr. www.Fringer.org

Sankar, Pamela (1992) State Power and Record-Keeping: The History of Individualized Surveillance in the United States, 1790-1935. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

Scott, James C. (1998) Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition have Failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Torpey, John (2000) The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Watner, Carl (2004) “’Your Papers, Please!’: The Origin and Evolution of Official Identity in the United States.” Voluntaryist, The Second Quarter.

Wilson, Thomas and Donnan Hastings (1998) Border Identities: Nation and State at International Frontiers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yuval-Davis, Nira and Pnina Weberner, eds. (1999) Women, Citizenship and Difference. London and New York: Zed Books.

30

[/img][/img]

[/img][/img]

Duidelijk nu?

Contested Citizenship: Cards, Colors and the Culture of Identification1

Pinkaew Laungaramsri

Introduction

On Friday September 8, 2005, more than 800 villagers from border communities of Tha Ton subdistrict, Mae Ai district, Chiang Mai province gathered before the Administration Court building in Chiang Mai as they listened to the reading of a verdict which ruled that a Mae Ai district office order to remove the name of 1,243 villagers from the household registration was unlawful. The court verdict came as a result of many years of local effort to regain their citizenship after it was revoked by the district office in February 2002. For Mae Ai district officials, the rationale for such revocation was based on their belief that these people were not “Thai.” This is simply because these people have never been permanent residents, as they constantly cross the borders between Thailand and Burma. Some of them have even obtained “the pink card,” the identification card for displaced person with Burmese nationality. Local people, however, argued that they once had the Thai ID card before moving out of the villages due to political turbulence between the Burmese army and ethnic insurgency in that area in 1971. Since they lost the Thai ID cards, their subsequent acquisition of “the pink card” was because of fear of deportation. District and local disputes went on for several years with no progress, as all the relevant documents stored at the district office which could have been used for verification were burned up in a 1976 fire accident. As a result, the Tha Ton villagers had no choice but to file a lawsuit against the Local Authority Department, and it was successful.

1 In Ethnicity, Borders, and the Grassroots Interface with the state: Studies on Mainland Southeast Asia in Honor of Charles F. Keyes, John Amos (ed.), Silkworm Books, Forthcoming

1

The politics of identification cards in the Mae Ai case is representative of the unsettling relation between state and citizenship in the border area. Over the past three decades, cards have become the strategic tool used by the state to differentiate the Thai from the non-Thai other. Issuance and revocation of cards for border-crossing people have become common state practices. At the same time, amendments of the Nationality Act are enacted now and then, changing the legal definition of a Thai citizen. As more colors have been assigned to new identification cards, cards and confusion about them increasingly complicate the interaction between state and people. And widespread card dispute and scandal proliferate.

In tracing the geneology of the scientific modes of classification of ethnic differences used by the modern nation-state in Asia, Keyes maintains that the political application of such science has not only resulted in the production of hierarchical order but also the fixing of national and thus ethic boundaries (Keyes 2002). These ethnological projects of classification undertaken in various countries of Asia, though based on flawed assumptions, have served as a powerful tool in differentiating between the national and the ethnic other. I would argue further that the ways ethnic classifications become operational in a society, as both tools of the state and a sign of its capacity, depend on an effective methodology. As Scott (1998:2-3) suggests, the modern state’s project to appropriate, control, and manipulate the cultural diversity of its inhabitants is carried out through tools of simplification and legibility, by “rationalizing and standardizing what was a social hieroglyph into a legible and administratively more convenient format" (p.2-3). In the case of Thailand, I maintain that a methodological tool that has powerfully rendered ethnic diversity legible is the system of identification cards, which serves a dual function of national embrace and dis-embrace. A product of the cold war era, such a system is not

2

merely a means by which the state controls populations but is constitutive of the sovereign nation-state itself. By tracing the history of the identification card system and shifting ideas of citizenship, this paper explores the changing relations between the state and its subjects. Inconsistent functions and meanings of cards assigned to different groups of people reflect the state’s unstable notions of citizenship and anxiety towards mobility. Who counts as “members” and as “different,” and where and when difference may legitimately be represented, are historically contingent. In the case of Thailand, the inherent instability in both the meaning and the limits of citizenship identity and difference is well-illustrated at the border whereas shifting card practices reveal the constant negotiation between forces of normalization and differentiation, and of national security and economic liberalization. As the state’s attempt to define people is often incomplete, the deployment of the state’s methods of identification among the people so designated always implies tension and contestation. Re-appropriation and reinterpretation of identification cards has been a strategic means of negotiation by the people classified as the non-Thai other. It is in this context that the notion of citizenship is often problematic, while the project of classifying and defining peoples will thus forever remain, as Keyes argues, “work in progress” (2002:1194).

The Embracing Citizenship

When the idea of citizenship was first introduced in Thailand in the early twentieth century, it was not really clear what it meant. Since the reign of King Chulalongkorn, colonial expansion has made it inevitable for the Siamese elite to rethink the once diverse ethnic conglomeration of Siam as a homogenous Thai nation, employing a European ideology of race. The creation of Thai nationality was carried out in the form David

3

Streckfuss calls “reverse-Orientalism”—the transformation of the other into Thai as a form of resistance against European colonialism. The materialization of “Thai nationality” was carried out by the subsequent King Vajiravudh (Rama VI). Interestingly, what concerned him was not how to define citizenship but rather how to turn the non-Thai subject into a Thai citizen. The Naturalization Act was then implemented in 1911, prior to the first Nationality Act in 1913. As Saichol (2005) notes, competing Chinese nationalism, widespread among overseas Chinese in Siam, was alarming, and one way to suppress the increasing mobilization and politicization of Chinese nationalist sentiment was through assimilation. The significant requirement of official naturalization was that those eligible to be citizens had to prove they had had at least five years residency in the Kingdom. At the same time, offspring of those with approved citizenship were automatically eligible to become citizens.

In the reign of King Rama VI, assimilation through legal naturalization served as a means to orient the people who the King defined as “born as Thai, being Chinese as vocation, registered as English” (Saichol, ibid.) and to transform them into Thais in soul and spirit. Legal naturalization was a characteristic strategy of “Thai-ization” (kan klai pen thai) and a state attempt at monopolization of the Thai nationalism. In keeping with the trajectory of transforming the multi-ethnic kingdom into an exclusive nation-state, the newly modern Thai state has continued to define Thai nationality by cultural qualities associated with the three elements of Thai language, Buddhism, and loyalty to the King. However, such effort at the homogenization of Thai national identity did not receive much of support by the Chinese, who constantly challenged the hegemonic notion of the Thai nation and thus rendered the project of assimilation problematic.

4

Despite the widespread propagation of Thai nationalism, Thailand’s 1911 Nationalization Act and 1913 Nationality Act did not define citizenship, nor its rights and obligations. If citizenship means “full membership in the community” (Marshall 1950), the nature of the legal bond between the members and their Thai community and an elaboration of what legal status of membership means is absent from the text. In the early period, citizenship was a somewhat ambiguous notion of incorporation that did not yet enter the realm of administrative apparatus. Although, a naturalization certificate was issued, it was not a national identification document and was not used by the state as a means for identity control. State’s attempt to regulate movement across national boundaries was also in its infancy. The unsettling notion of a means of embracing citizenship, with loosely regulatory mechanisms, thus allowed for the possibility of interpretation and negotiation. As a result, for non-Thai, particularly Chinese, to be Thai or not to be Thai remained a political and cultural choice which could be maneuverable. . However, such possibility became increasingly difficulty with the development of a state identification card system in the middle of the twentieth century.

Culture of Identification and the Proprietary Citizenship

Since 1932, in the post-absolute monarchy era, official thinking about citizenship has undergone a significant shift. Under the regime of Phibun Songkram, Thai race (chonchat thai) had been emphasized as the significant trait of Thai nationality. The emphasis on Thai race as the basis of nationalism served multiple purposes--to undermine the previous idea of Thainess centered around the allegiance to the monarchy, to exclude

5

the Chinese from the political sphere, and to provide a protective ring against communist expansion (Saichol 2005, Keyes 2002). At the same time, the dream of a unified Thai nationality extended across national boundaries, culminating in a short-lived pan-Thai movement (see Keyes 2002, Crosby 1945). It was also in the reign of Phibun Songkram that “Thai” was turned into an official identity making people’s identities and nationality within the boundary of the nation-state. In 1939, Siam was renamed Thailand, the country that defined “Thai” as its culture, citizenship, and territory. In 1943, the regime launched a first experimental identification card, authorized by the Identification Card Act. This card applied to Thai who resided in Pranakorn (Bangkok) and Thonburi provinces.

The invention of Thai identity cards used in conjunction with the household registration document represents a new method of the Thai state authority to circumscribe, register, regiment, and observe people within their jurisdictions. The identification card as a form of state power was necessary not only because of the bureaucratic control it entailed, but also because it implied the establishment of citizenship by binding body, identity, and citizenship together. It is worth noting that state inscription on population is by no means a recently modern project. In pre-modern Siam, the most effective control of corvee labor was carried out through methods of body marking, the tattooing of the wrist of a phrai luang (commoner who worked for the King), identifying the name of city and master.

Unlike tattooing and other pre-modern forms of registration, the purpose of modern state inscription through identification card is not for labor control but to ensure the national loyalty of the subject of the state. The card has also brought with it the notion of proprietary citizenship that allows the state to maintain direct, continual, and specific contact between its ruling bureaucracy and its citizenry. However, one enduring problem

6

the state faced in constructing a system of official identification was how to articulate identity to a person/body in a consistent and reliable way. As body and identity has never been in permanent or fixed connection, the task of describing identity accurately and consistently was a major challenge to the state. Thorough technologies must then be designed to facilitate the identification process. Binding identity to the body was thus done by technologies which included photographs, signatures, and fingerprints, and by the use of legal practices, for example, the requirement to carry identification cards at all time.

Picture 1: The first Thai identification card (1943)

Picture 2: The second Thai identification card (1963)

7

8

Picture 3: The third Thai identification card with 13 digits (1988)

Picture4: The fourth Thai identification card with magnetic stripe(1996)

Picture 5: The smart card (2006)

The state’s notion of proprietary citizenship through the enforcement of identification cards has not only served to fix identity and loyalty as subject to one nation- state, but has also been used as a powerful tool to discipline stubborn/bad subjects. In the history of suppression tactics, identification card inspection has been employed as a state’s means of surveillance and punishment against popular demonstrations and political movements. The historical construction of official Thai identity epitomizes the state’s attempt to establish a form of ownership over individual citizens, reflected in different technologies of identification. Proprietary citizenship has been exercised through the making of a permanent, indelible identity which is lasting, unchangeable, always recognizable and provable. Identification cards as a function of state capacity to create documentary evidence and bureaucratic records have enabled the state to recognize specific individuals. Official Thai identity acquires its meaning and power not only through the system of classification but also through the active interactions with the state machinery which constantly monitors, regulates and guides personal conduct, thus legitimizing the state’s intimate bond with its citizen.

Cards, Colors and the Contingent Citizenship

Although citizenship is commonly regarded as a matter of the relations between individuals and the state to which they belong, it is also one of the markers used by states in their attempt to regulate the movement of people across borders. Citizenship at the border is often historically volatile, reflecting the state’s changing view towards border and mobility. In its transformation towards the modern nation-state, government of people gave way to government of territory, so the need for clearly bounded divisions of ownership and control correspondingly increased, with the border becoming a state weapon (Wilson and Donnan

9

1998:8-9). Nevertheless, the effective control of territory also depends on the way in which identity can be effectively regulated.

Despite the fact that immigration has been always central to the process of nation- building, the historical connection between route and root (Clifford 1997) as basis of societal formation has often been written out of the collective memories of the modern nation-state. Fluid boundaries have been suppressed by territoriality as one of the first conditions of the state’s existence, and the sine qua non of its borders (Wilson and Donnan 1998). As Castles and Davidson (2000) note, the regulation of immigration is only a recent phenomenon, dating from the late nineteenth century, while state policies to integrate immigrants or regulate ‘community relations’ date only from the 1960s. Yet, assimilation and differential exclusion have been made natural and inevitable processes of what Castles and Davidson call the controllability of difference (ibid.).

Whereas borders represent spatial and temporal records of relationship between people and state, such records often include the state’s anxiety towards mobility across national boundaries. Contingent citizenship is therefore a product of shifting state-ethnic relations at and across borders as mediated by diverse ideological and political economic forces at different periods of time. Such forces, which oscillate between inclusion and exclusion, have been played out both symbolically and concretely, constituting a “politics of presence,” as “an embodied enactment of toleration or intolerance” (Yuval-Davis and Werbner 1999:4). In the case Thailand, the politics of presence is well illustrated in the complex yet arbitrary systems of identification cards at the border.

The post-World War II borders of Thailand can be characterized by a tension

10

between national security ideology and forces of economic integration. Between 1965- 1985, borders have become highly politicized with the migration influx of refugees, displaced people, and political asylum seekers. On the Thai-Burmese border, the Thai state indirectly supported the armed forces of ethnic minorities that were fighting the government of Burma, as a kind of “buffer state” (Caouette, Archavanitkul, and Pyne 2000). The security policy of this period was designed in order to prevent the invasion of communism from nearby countries (ibid.). It was in this period that the so-called “colored cards” (bat si) were designed as a means of securing the borders through certifying individual identity and controlling movement across the border. Most of these diverse identification card programs were poorly planned and lacked consistent rationales (e.g., what counts as immigrant can vary depending on date of entry into Thailand, ethnic identity, and political history), resulting in confusion rather than effective measures of control. Throughout the two decades of “colored cards” and registration of people classified as non-Thai others, the implementation of differential exclusion has often been in a state of flux. For example, some cards might be eliminated, leaving the card holders with no future, while others were upgraded to a Thai identification card. After 1989, with the waning of the cold war era, borders acquired new meaning as a gateway to economic integration. New types of cards have been invented for “alien labor” (raeng ngan tang dao), as a means to both regulate the flow of cross-border immigrants and reap benefits from new economic resources. While controversy regarding alien identity cards has escalated and the demand for Thai identification cards among hill people and migrant workers has intensified, “ID card scams” have become widespread, adding further chaos to the colored card scheme.

Table 1 Chronology of Implementation of “Colored Cards” for Non-Thai Citizens in Thailand

11

1969- Hill Tribe Coins 1970

1970 Former Kuo Min Tang Soldier ID Cards

(White Cards)

No longer in use.

Issued by Depart of Administration

Cabinet Resolution on 6/10/1970 assigned immigrant status to former KMT soldiers. Cabinet Resolution on 30/05/1978 allowed legal naturalization of former KMT soldiers for their contribution to the Thai nation (fighting communists).

Cabinet Resolution on 12/06/1984 allowed children of former KMT soldiers to

Used as verification of settlement in Thai Kingdome between 1969- 1970.

Widespread selling of coins and difficulty in establishing proof. Three batches of IDs have been issued.

12

Year

Identification Cards

Status

1967

Vietnamese Refugee ID Cards (White Cards with a Blue Border)

Children of Vietnamese Refugees who entered into Thailand between 1945-1946 were eligible for Thai citizenship.

Vietnamese refugees who have not acquired Thai citizenship must ask permission from governors before traveling out of residential provinces.

Issued by Police Department

1st batch

Issued :24/08/67 Expired:23/08/1973 2nd batch Issued:2/08/1980 Expired:1/08/192 3rd batch extended 2nd batch to 3/12/1988

4th batch

Issued: 19/07/1990 Expired:18/07/1995 5th batch Expired:26/08/1997

13

1976 Immigrants with Thai Race from Ko Kong,

Cambodia

(Green Cards)

acquire Thai citizenship. Those who have not yet acquired Thai citizenship must ask permission from governors before traveling out of residential province.

Issued for former Thai citizens and their children whose citizenship was removed when Ko Kong was returned to Cambodia.

Three batches were issued between 1976-1989

1977